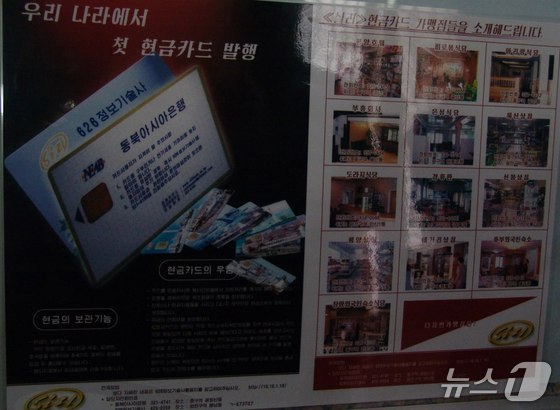

On May 13, 2006, the author joined JoongAng Ilbo’s reporting team for lunch at the Arirang Restaurant along the Taedong River in North Korea. At the entrance, an advertisement caught the eye, promoting the Silri card issued by the Northeast Asia Bank. It boldly proclaimed, “The first cash card in our country.” The reason for our North Korean guide’s choice of this unfamiliar restaurant became clear – they wanted to showcase their inaugural bank card.

Launched in 2005, the Silri card allowed deposits and withdrawals in North Korean currency and six foreign currencies. However, its use was limited to about ten restaurants and shops at the time.

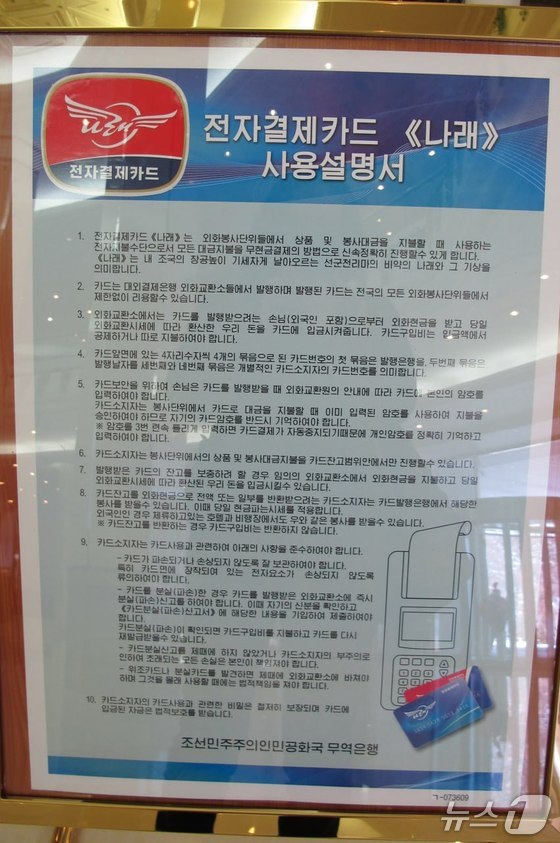

Five years later, the Korea Trade Bank introduced the Narae electronic payment card, available in blue for locals and red for foreigners. Users could either preload foreign currency or use it as a debit card linked to their accounts. Soon after, other commercial banks like Koryo, Seonbong, and Geumbit followed suit with similar offerings. The network of participating merchants expanded significantly to include hotels, restaurants, and major stores. Rechargeable transit cards for buses and subways also hit the market.

In 2015, the Central Bank of North Korea unveiled the Jeonseong card, enabling basic financial services such as payments, remittances, and withdrawals. Initially, it was primarily used to send small amounts to children serving in the military. At the time, skepticism prevailed about North Koreans embracing electronic cards, given their distrust of banks and unfamiliarity with card usage.

However, the landscape began to shift with the emergence of e-commerce platforms like Okryu and Manmul Sang, coupled with the government’s active promotion of card usage. The adoption of Jeonseong and Narae cards surged. By 2019, North Korean data showed that Manmul Sang had evolved into a thriving online marketplace, featuring over 400 North Korean companies offering 450 product categories. The platform even launched a mobile app.

Taking a bold step forward, North Korean authorities enacted the Electronic Payment Law in 2021 (amended in 2023), mandating card use for institutions and residents alike. Following a trial period, farm workers nationwide began receiving their in-kind distributions via Jeonseong cards by late last year, replacing cash payments. Early this year, the system expanded to all employees of institutions and enterprises, who now receive their wages electronically. In February, Han Nam-cheol, secretary of the Shincheon County Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, highlighted in a Workers magazine article that every farm household now had access to Jeonseong cards for direct cash distributions. This marks a significant shift, with most economically active residents now receiving and spending their earnings via cash cards.

The proliferation of card issuance and usage among North Koreans has paved the way for various electronic payment systems, coinciding with the spread of smartphones. North Korea defines these systems as new cash transaction platforms enabling users to pay for services and fees using smart devices. They’ve also incorporated QR code-based quick payment features.

In 2020, the Central Bank of North Korea and the Pyongyang Information Technology Bureau’s Card Research Institute jointly launched the first smartphone-based electronic payment system, Jeonseong. Since then, various institutions and companies have rolled out electronic payment programs like Gangseong, Ullim, and Samheung, steadily growing their user base. Notably, the Samheung Electronic Wallet, developed by the acclaimed Samheung Economic Information Technology Company, reportedly boasts millions of subscribers. North Koreans can now link their personal or business cards to online shopping platforms and mobile phones for a wide range of consumer activities.

The 2023 amendment to the Electronic Payment Law goes a step further, imposing fines on institutions, enterprises, organizations, or citizens failing to adopt the electronic payment system. This effectively makes electronic payments mandatory for all residents. Basic credit cards allowing post-paid transactions have also been introduced, cementing card usage and electronic payments as a requirement rather than an option for North Koreans.

For several years, North Korean authorities have been aggressively promoting financial informatization. They’ve pushed this policy, citing the need to ensure smooth financial operations and bolster national finances.

Financial informatization is a global trend aimed at enhancing transparency, convenience, and efficiency in finance while reducing transaction costs. North Korea has embraced this trend, recognizing information technology as a key factor in international competitiveness. They’re introducing various new technologies, including mobile devices and artificial intelligence (AI) based services, to develop related technologies and modernize their lagging financial sector. It’s likely they carefully studied the experiences and potential pitfalls from other socialist economies like China and Vietnam before implementation.

In practice, North Koreans are experiencing the convenience of easy remittances and simplified change calculations through card usage. The younger generation, in particular, appreciates the ability to make payments at state-run stores, registered private shops, and online marketplaces with just a mobile phone. For those less familiar with digital technology, the government is conducting regional financial education programs to ease the transition to card and electronic payment systems.

Beyond user convenience, North Korea appears to be leveraging this shift to regain control over private finance, which flourished as trust in banks declined. By reducing cash circulation and expanding cashless transactions, they aim to regulate individual currency exchange operators, remittance workers, and loan sharks while closely monitoring fund flows. These measures are expected to boost national finances and bank revenues. They also facilitate socioeconomic control, making it easier to prevent bureaucratic corruption and track the assets of the wealthy and market liquidity. This explains why some North Koreans express concerns about potential state surveillance, despite acknowledging the system’s convenience.

In the two decades since the introduction of cash cards, North Korea has seen a dramatic increase in card issuance and electronic payments. The society has transformed from one without bank cards to one where carrying at least one card is the norm. In North Korean parlance, this represents a quantum leap in the financial sector. The younger generation now routinely uses mobile payments for everything from school transportation to purchases at school stores and local markets, as well as downloading apps and paying for online games. Even older adults, less familiar with digital devices, are adapting to this new socialist financial order as their wages are deposited electronically.

This social transformation is poised to impact not only the growth of North Korea’s fintech industry and residents’ daily lives but also future international exchanges and cooperation, including foreign investment attraction and tourism expansion. Moreover, it may help bridge the digital divide between North and South Korean youth, potentially opening avenues for cooperation in digital finance as inter-Korean relations evolve.