Two years ago, I chose Iran as my summer vacation destination. Looking beyond the frequent headlines about nuclear weapons, U.S. sanctions, and anti-Israel sentiments, I wanted to experience the essence of the ancient Persian Empire. I was also curious to explore Iran from within, a country labeled as a rogue state by the United States.

During my two-week visit, Iran’s negative image not only dissolved but transformed into a surprisingly positive experience. This change stemmed from encounters with locals: a young girl learning Korean because of her love for BTS, a woman who had watched the Korean drama “Jewel in the Palace” three times, and an elderly gentleman who personally guided me from the subway station to the bus terminal to prevent me from getting lost.

International sanctions led by the U.S., an oppressive government, and nuclear weapons — Iran’s circumstances naturally invite comparisons with North Korea. Just as the Iranian people helped reshape their country’s negative image, I wonder if we could change perceptions about reunification in South Korea, especially among the younger generation, by emphasizing our shared humanity.

However, discussing North Korean citizens in South Korea is a delicate matter. While human rights issues are generally seen as part of a progressive agenda, the mere mention of North Korea creates an ironic reversal in public discourse.

Depending on the political climate, North Korean human rights issues oscillate between being used as a diplomatic bargaining chip and a tool for pressuring Pyongyang. Typically, conservatives highlight human rights violations to criticize North Korea, while progressives emphasize dialogue over these concerns.

The Lee Myung-bak administration elevated the investigation of North Korean human rights conditions to an official project. The Park Geun-hye government enacted the North Korean Human Rights Act and widely publicized human rights violations, whereas the Moon Jae-in administration faced controversy over the forced repatriation of North Korean fishermen and halted the publication of the White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea.

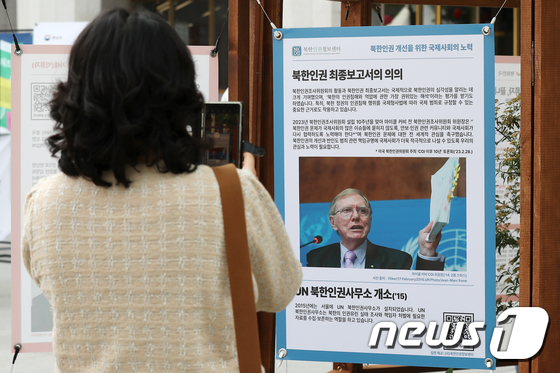

With the arrival of the Yoon Suk Yeol administration, North Korean Defectors’ Day was established, and the first public North Korean Human Rights Report was released.

The Database Center for North Korean Human Rights (NKDB) claims that since its inception in the late 1990s, it has been affected by ideological and partisan conflicts with each new administration.

Similarly, the Transitional Justice Working Group (TJWG), which focuses on North Korean human rights, has reported difficulties in advancing programs based on the changing administration’s stances. While the change in government resolved various issues, concerns persist about a potential regression in addressing North Korean human rights.

Interestingly, unlike in the political sphere, ordinary citizens express concern about North Korean human rights issues across political affiliations. A survey conducted by NKDB last October revealed that 72.9% of conservative respondents and 68.5% of progressive respondents expressed worry about North Korean human rights, indicating a disconnect between political discourse and public sentiment.

The issue of North Korean human rights is so sensitive that it is often referred to as Kim Jong Un’s Achilles’ heel. Nevertheless, it seems inevitable that we must address North Korean human rights as a universal and non-partisan agenda rather than as a tool for specific political factions.

If the government’s North Korean human rights policies are swayed by political judgments, we will not achieve effective improvements. It is questionable whether using human rights issues as leverage in inter-Korean relations will effectively influence North Korea. Instead, maintaining consistency in North Korean human rights policies might be the way to bring about change, fostering the perception that North Korea cannot impact South Korea’s policies.